Civil services often employ various strategies to avoid accountability when commissioning or conducting reviews of their conduct. These strategies can significantly undermine the transparency and effectiveness of the review process, skewing the results to their benefit and to the detriment of the public. Here are some common mechanisms:

- Narrow Terms of Reference (TOR): Setting TOR that exclude key issues or areas of misconduct limits the scope of the review, preventing thorough investigation. This tactic ensures that the review focuses on less sensitive areas, avoiding direct scrutiny of responsible individuals.

- Controlling the Review Process: By commissioning the review internally and setting the TOR themselves, civil services can steer the investigation away from sensitive areas, ensuring that the review does not uncover unwanted details.

- Confidentiality and Redactions: Implementing confidentiality clauses and redacting significant portions of the source documents or report under the guise of data protection laws can obscure critical information, limiting the transparency of the findings. Sometimes whole pages are redacted and it is noted that this situation is getting worse – to the extent that it cannot be determined to what an entire document relates.

- Delaying Information Release: Postponing the release of essential documents or reports can reduce public and media scrutiny. By the time information is released, public interest may have waned, diminishing the impact of any revelations.

- Focus on Systemic Issues: Emphasizing systemic or procedural failures rather than individual accountability diffuses blame across the organization, avoiding pinpointing specific individuals for misconduct.

- Future-Oriented Recommendations: Shifting the focus to future improvements and recommendations rather than past actions allows the narrative to move away from accountability, making the review seem constructive while avoiding addressing past failures directly.

- Choosing a Compliant Reviewer: Selecting a reviewer likely to deliver favourable outcomes due to personal or professional ties, dependency, or shared viewpoints can result in a biased review. This choice ensures that the review is sympathetic to the interests of those commissioning it.

- Legal Privilege: Withholding information under the pretext of legal privilege prevents scrutiny of sensitive documents or communications that could reveal misconduct. Pretending that the lawyer holds the privilege so the CS ‘can’t’ release material.

- Losing Evidence: Misplacing or destroying crucial evidence intentionally hinders the review process and protects those involved from accountability.

- GDPR Mismanagement: Misapplying data protection regulations can limit the disclosure of information, shielding individuals from scrutiny.

- Complex Reporting: Producing overly complex or technical reports can obscure key findings and make it difficult for stakeholders to understand the issues, reducing the report’s effectiveness and impact.

- Limited Stakeholder Engagement: Restricting input from external stakeholders or affected parties helps control the narrative and outcomes of the review, ensuring that dissenting voices are minimized.

- Inadequate Resources: Providing insufficient resources or time for the review ensures that it cannot be conducted thoroughly, leading to superficial findings.

- Internal Reviews: Opting for internal reviews rather than independent ones increases the likelihood of bias and self-censorship, protecting the interests of those involved.

- Undermining the Whistleblower or Complainant: Civil services may discredit or retaliate against whistleblowers or complainants to undermine their credibility and divert attention away from the allegations. This can include character assassination, professional isolation, or legal actions against the whistleblower and/or labelling them as ‘vexatious’ and ‘malicious’.

- Making embarrassing content unindexable: For material that has to be released, converting an ‘offending’ portion of the document from text to images solves the problem. Search engines don’t OCR these images back into the text to index them, so the content is much harder to find1.

- Not publishing: ‘Forgetting’ to publish awkward findings makes them ‘go away’.

These mechanisms collectively undermine the review process, making it difficult to achieve transparency, accountability, and meaningful reform. Such techniques can be especially potent and effective in a small community.

If you have evidence of such behaviour, please get in touch with me.

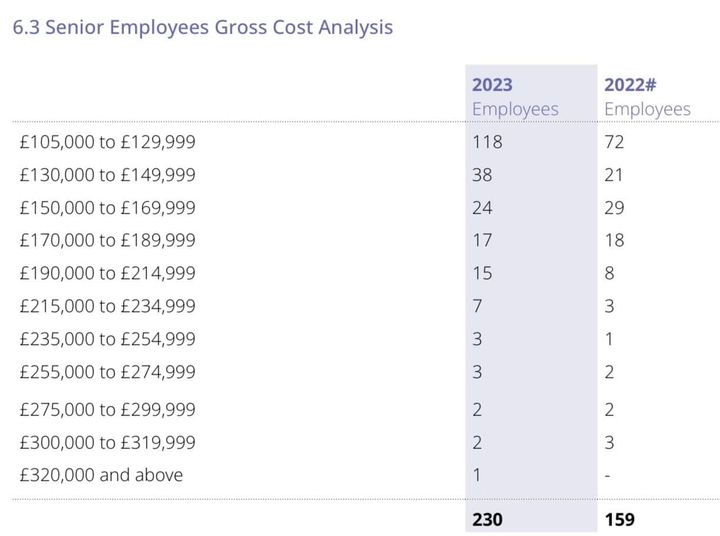

How much do we in Guernsey pay our senior civil servants for such fun and games?